Friday, 24 November 2017

Volunteer Stories: Wandering and wondering about Warrington

Kath and Joan didn't know each other when they began volunteering here, they are now a crack team and firm friends, having worked their way through 2,764 (and counting) Warrington Borough Council building plans - removing old acidic envelopes, repackaging, inspecting and cataloguing - making them searchable and accessible for the first time. Here they reflect on their experience ...

It usually seems that the rich and powerful leave the better preserved records and artefacts. This is not always the case in the drawings for planning permissions granted by Warrington Borough Council in the early 1880s. It is the less well-off doing their own drawings on rougher quality paper whose records are usually better preserved. The architects used tracing paper for the block plans, ground plans, elevations and sections for the better off clients. Unfortunately, as Angela, one of the conservators here explains ‘Transparent papers do not age well and are often found in poorer physical condition than non-transparent papers of the same age. They were exposed to acids, impregnated with oils or manufactured with over-beaten fibres to give them their transparent qualities. Oxidation and acid hydrolysis will cause discolouration and cause the paper to become brittle and prone to cracking.’ Fortunately, the main architects of Warrington, William Owen, Robert Curran, and Pierpoint & Adams, usually write an accompanying letter which contain the salient facts - where, what and for whom. A glimpse of social mobility is provided during this period when John Wright from his letterheads moves from being a builder to an architect in the town.

Planning permission provides a fascinating snapshot of the development of Warrington in the late 19th century. There are applications to build new streets of terraced houses which have to be built in accordance with the local bye-laws, brick built, slate roofed and with drainage to sewers as well as with closets in the yards. 'To be drained as shown with glazed socket drain tiles laid with proper fall and clay puddled joints into the present nine inch sewer in Porter Street' (1882, Mr William Hewitt). Bathrooms and indoor closets are the preserve of the rich in the borough. Yet James Parkinson wants to convert a kitchen and lumber room to a photographic studio complete with dressing room, preparing room and darkroom and an indoor closet in 1883. The names of the developers and landowners are a fascinating mix of the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ men of Warrington: a map drawn up in 1882 of the land owned by the Honourable Leopold W H Powys shows numerous new streets with no names available for leasing to builders in Little Sankey. The names of the developers including John Appleton and William Porter keep on reoccurring.

Applications for planning permissions not only provide information about the architects, builders, and the landowners but also reveal how the borough was developing otherwise. Schools are being built or altered; some include a house for the teacher as well as the separate girls’ and boys’ entrances, classrooms and playgrounds. Is it a case of desperate measures in a very last-minute application to build two closets at Bank Street School before the “schools open again on Monday next.”?

Entertainment is also provided for: an application was received from Mr Harmston for a temporary erection of a circus tent in 1881 complete with side elevations and a ground plan showing the seating, an orchestra pit and stabling (above). In 1883 Mr Brinsley Sheridan applied to construct a new theatre on Scotland Road (below).

Commercial premises also reflect new standards, when in 1883 a new fish warehouse had to comply with the standards laid down by the Local Board of Health. Even the man who converted his front room and bedroom above to a temporary stable and hayloft had to make sure that there was no direct access to these new features from the rest of his house.

Talking of stables, there is no greater contrast between the rich Captain Sylvanus Reynolds’ substantial architect-designed brick built stable house with accommodation for the coach man and four horses and the distinctly less wealthy Mr W Owen wood shippon stable for four horses to be built on waste land off Ellesmere Street as shown on the rough sketch drawn by him which comprises his planning application.

There is also evidence of the growing wealth of women, who owned property and were active in its development or alteration at a time when married women’s possession (and they themselves) were the property of their husbands. Mrs Ann Jackson applies for permission to build a slaughter house and stable in Church Street, and Mrs Harriet Woods owns houses on Church Street and a druggist shop on the corner of Church Street and Orchard Street and more cottages on Orchard Street and wants to build a warehouse between the druggist and the cottages.

Finally, just to prove that there is nothing new in the current fashion for artisan coffee, Mr Geddes wants to build a new warehouse at the junction of Peter Street and Market Street for his coffee roasting room and shop.

Wednesday, 22 November 2017

Volunteer Stories: Connecting with a collection

In 2016, Sandbach High School student Zia Duncan first began examining our collection relating to the Knutsford Ordination Test School (collection reference D 3917). She had this very personal and emotional response to the material ...

It has been just over a century since the beginning of World War One in 1914, a war that lasted four years but took millions of lives away from families across the world. But for the ones that survived, they came back to a home that was very different. Boys who were pulled out of having an education at fifteen or sixteen came back as men who lacked the knowledge and training for future careers as the years that were supposed to be spent in school had been replaced by living in a trench. Their prospects seemed dim, especially for the poorer classes who could not afford the cost of re-learning all their missed years.

Using newspaper articles, photographs and written histories related to the school I was able to research the incredible story of the men who had had the courage and bravery to fight but now wanted to build a future for themselves. The building chosen to house this school was originally Knutsford Gaol, which had been occupied by German prisoners during the war. Due to the housing shortage it was one of the few remaining buildings left that could house the number of men, although it was grim, dirty and out-dated. After enduring the trenches, there were initially some doubts as to how the men would take the news, but fortunately they rose to the occasion. The students arrived at their new school on the 26th March 1919. The advance party, which was aided by a few local well-wishers, had worked very hard to get it ready in time (which meant cleaning up the mess of the German prisoners). Men would now enter their first term at Knutsford with “gallant and high-hearted happiness”.

Despite the obstacles that the residents of the Test School had to face, many of them completed their education in the subjects of History, Natural Science, English Literature and Greek (or Latin) to Test Examination standard and set themselves on the road for higher ambitions. For example, by the end of the Summer term in 1920, 155 men left for further education, 111 for universities and 44 for theological colleges. Through the dedication of the local people and the well-wishers who helped transform the dirty Gaol into a school, the former soldiers of a dreadful world war had managed to set themselves up for a bright, well-deserved future.

Volunteer Katherine Treacher has continued working on the collection as we anticipate there may well be interest in this remarkable institution in its centenary year in 2019. The collection has inspired her to visit sites connected with the School, including St John's in Knutsford where the men went to church. She continues the story ...

The primary aim of the Knutsford Ordination Test School was to educate young men from all backgrounds returning from the First World War having missed out on higher education, with a view to them following their vocation to become priests. The school spent two years equipping the men with an education that would give them access to theological college or university to progress on to ordination. The ‘test’ part of the school’s ethos referred to the testing of each student’s commitment and suitability for clerical life. One well-known figure involved in the teaching at the School was the Reverend Philip ‘Tubby’ Clayton of the Toc H movement.

By 1922 the Church of England had stopped funding the school and it became a voluntary organisation. With this came the necessity for the School to raise all its own funds and provide student bursaries with limited outside support. From then on the School’s existence seems to have been dogged by struggles to raise enough money to stay open.

The archive contains many interesting documents including Annual Reports that chart the progress of the School from its early beginnings until the early 1940s when funding became extremely challenging. They record the progress of the school from Knutsford Gaol, now the site of Booths supermarket, to the Hawarden Old Rectory, now the Flintshire Record Office. The School had moved briefly in the early 1920s to a large house near Knutsford Common but struggled to operate in cramped conditions. In 1925, the Gladstone family gifted the Old Rectory at Hawarden (new) Castle and £3000 for building works to enable the creation of a new, spacious school in grounds of nearly eight acres.

The Annual Reports also record the wide variety of activities, giving an impression of a lively and vibrant community involving sporting events, fêtes, festivals, musical concerts, plays, lectures, lantern shows and Quiet Days led by local bishops and other religious visitors. As the number of ordained old boys from the school grew, so subscriptions and donations from their parishes grew, helping to make the heyday of the school the late 1920s. The archive also includes copies of the School magazine Ducdame and magazines of the Knutsford Fellowship dating until the early 1970s.

There is also a card index which contains what appear to be the records of all the students who attended the School and notes about their nature, attendance and later careers. Comments such as ‘fond of girls…sacked!’ and ‘chief interest cars and films,’ are amongst the more colourful. This information might be of particular interest to researchers interested in tracing an ancestor who attended the School. Amongst other items that might be of interest are playbills, copies of exams, minutes, letters, Knutsford Fellowship directories and numerous photographs of the men. A number of photographs have names on the back or are early, signed studio portraits, but many more of these are not named. However, the spirit of School is apparent in the numerous group shots which emit happiness and pride.

It has been just over a century since the beginning of World War One in 1914, a war that lasted four years but took millions of lives away from families across the world. But for the ones that survived, they came back to a home that was very different. Boys who were pulled out of having an education at fifteen or sixteen came back as men who lacked the knowledge and training for future careers as the years that were supposed to be spent in school had been replaced by living in a trench. Their prospects seemed dim, especially for the poorer classes who could not afford the cost of re-learning all their missed years.

Using newspaper articles, photographs and written histories related to the school I was able to research the incredible story of the men who had had the courage and bravery to fight but now wanted to build a future for themselves. The building chosen to house this school was originally Knutsford Gaol, which had been occupied by German prisoners during the war. Due to the housing shortage it was one of the few remaining buildings left that could house the number of men, although it was grim, dirty and out-dated. After enduring the trenches, there were initially some doubts as to how the men would take the news, but fortunately they rose to the occasion. The students arrived at their new school on the 26th March 1919. The advance party, which was aided by a few local well-wishers, had worked very hard to get it ready in time (which meant cleaning up the mess of the German prisoners). Men would now enter their first term at Knutsford with “gallant and high-hearted happiness”.

Despite the obstacles that the residents of the Test School had to face, many of them completed their education in the subjects of History, Natural Science, English Literature and Greek (or Latin) to Test Examination standard and set themselves on the road for higher ambitions. For example, by the end of the Summer term in 1920, 155 men left for further education, 111 for universities and 44 for theological colleges. Through the dedication of the local people and the well-wishers who helped transform the dirty Gaol into a school, the former soldiers of a dreadful world war had managed to set themselves up for a bright, well-deserved future.

Volunteer Katherine Treacher has continued working on the collection as we anticipate there may well be interest in this remarkable institution in its centenary year in 2019. The collection has inspired her to visit sites connected with the School, including St John's in Knutsford where the men went to church. She continues the story ...

The primary aim of the Knutsford Ordination Test School was to educate young men from all backgrounds returning from the First World War having missed out on higher education, with a view to them following their vocation to become priests. The school spent two years equipping the men with an education that would give them access to theological college or university to progress on to ordination. The ‘test’ part of the school’s ethos referred to the testing of each student’s commitment and suitability for clerical life. One well-known figure involved in the teaching at the School was the Reverend Philip ‘Tubby’ Clayton of the Toc H movement.

By 1922 the Church of England had stopped funding the school and it became a voluntary organisation. With this came the necessity for the School to raise all its own funds and provide student bursaries with limited outside support. From then on the School’s existence seems to have been dogged by struggles to raise enough money to stay open.

The archive contains many interesting documents including Annual Reports that chart the progress of the School from its early beginnings until the early 1940s when funding became extremely challenging. They record the progress of the school from Knutsford Gaol, now the site of Booths supermarket, to the Hawarden Old Rectory, now the Flintshire Record Office. The School had moved briefly in the early 1920s to a large house near Knutsford Common but struggled to operate in cramped conditions. In 1925, the Gladstone family gifted the Old Rectory at Hawarden (new) Castle and £3000 for building works to enable the creation of a new, spacious school in grounds of nearly eight acres.

The Annual Reports also record the wide variety of activities, giving an impression of a lively and vibrant community involving sporting events, fêtes, festivals, musical concerts, plays, lectures, lantern shows and Quiet Days led by local bishops and other religious visitors. As the number of ordained old boys from the school grew, so subscriptions and donations from their parishes grew, helping to make the heyday of the school the late 1920s. The archive also includes copies of the School magazine Ducdame and magazines of the Knutsford Fellowship dating until the early 1970s.

There is also a card index which contains what appear to be the records of all the students who attended the School and notes about their nature, attendance and later careers. Comments such as ‘fond of girls…sacked!’ and ‘chief interest cars and films,’ are amongst the more colourful. This information might be of particular interest to researchers interested in tracing an ancestor who attended the School. Amongst other items that might be of interest are playbills, copies of exams, minutes, letters, Knutsford Fellowship directories and numerous photographs of the men. A number of photographs have names on the back or are early, signed studio portraits, but many more of these are not named. However, the spirit of School is apparent in the numerous group shots which emit happiness and pride.

Tuesday, 21 November 2017

Volunteer stories: Record Office staff get cooking

For our popular 'Cooking the Books' event staff at the Record Office volunteered their time and culinary skills to recreate recipes from the archives ... here is a modern take on the 18th century cook and businesswoman Elizabeth Raffald's herb pie!

Just nine lines of recipe but how to recreate the pie in a modern kitchen? I began with groats … any grain with the husk still on. Thought about going a bit Ottolenghi with freekeh which could work nicely with the other flavours but settled on pot barley to remain authentic local.

I decided early on that I wouldn’t be adding a pound of butter at the end but would cook with butter throughout – I wondered if the reasoning behind boiling all the ingredients and then adding such a large quantity of butter was to do with how tricky it may have been to control the heat on domestic fires and ranges so risk burning it, but how vital it would have been for flavour and calories during Lent? The fact that Elizabeth mentions the option of a raised crust made me opt for hot water crust pastry.

Serves 4-6

For the filling

75g unsalted butter

1 large onion, diced

200g pot barley

1 large leek, sliced

parsley

lettuce

beetroot tops or chard

baby leaf spinach

2 apples, sliced

For the pastry

300g plain flour

75g butter

75g lard

135 ml hot water

salt

1 egg

Take a large saucepan. Gently cook the onion in 25g of the butter, stir in the barley to coat and add enough boiling water to cover. Leave to simmer for around 40 minutes, topping up with boiling water as necessary. Test the barley can be bitten, turn off the heat and leave to cool with the lid on, any remaining liquid should be absorbed.

Make the hot water crust pastry. Rub the butter into the flour until it looks like fine breadcrumbs. In a small pan on a gentle heat melt the lard in the hot water, then pour onto the flour mixture. Mix with a knife and bring it together into a ball. Leave to cool until room temperature and finish making the filling.

Take a deep frying pan and gently fry the leeks in the remaining butter. Roughly chop enough lettuce, parsley and beetroot tops or chard to match the quantity of leeks and add them to the frying pan with the same quantity of baby spinach leaves. (If using chard add the chopped thicker stalks at the same time as the leeks). Cook until the leaves have collapsed and stir in the sliced apple and groats. Season well with salt and pepper to taste.

Roll out two thirds of the pastry and line a ten inch square baking tin. Add the filling and top with a lid rolled from the remaining pastry. Press the edges together and beat the egg with a pinch of salt and brush onto the pie.

Place in the middle of the oven preheated to 180 degrees centigrade and bake for about an hour, the pastry will be golden brown.

Monday, 20 November 2017

Volunteer Stories: Records of the Ridge

A ‘stray item from the archives of Merriman, Porter and Long, solicitors of Marlborough’ arrived on the archivist’s desk, transferred to Cheshire Archives from the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre. The same archivist who, a few months earlier, had run a training session for volunteers embarking on a project to research and locate documentary and physical evidence of quarrying on Cheshire’s Sandstone Ridge. There were quarries marked on this map of Manley – the archivist alerted the group to the new arrival … David Joyce, volunteer with the Ridge, Rocks and Springs project completes the story …

“A tin case containing some old plans of lands seemingly of no use” reads the faded, discoloured, remnant of the original wrapper inside Cheshire Record Office folder D8835. How wrong this was.

The staff at the Record Office had kindly directed us to this treasure and it provides a fascinating insight into the Manor of Manley. The accession contains four maps of Manley. The separate sections are marked north, south, east and west quarters and include instructions how to overlap them to make the complete manor. The heading of the maps is “A Plan of the Manor of Manley belonging to Jocelyn Deane Esq 1777 taken from an original plan for Robert Davies Esq 1722.”

We have been researching Manley as part of the Sandstone Ridge Trust ‘The Ridge Rocks and Springs’ project funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund. The project is looking at quarries, ancient water supplies and historic graffiti along Cheshire’s sandstone ridge.

Previous research suggests that Manley quarry has been in use since Roman times but there are two main quarries in the parish and it is often difficult to distinguish between them when reference is being made to ‘the quarry’. One is usually known as Manley Quarry, and the other one is on Simmonds Hill. These maps clearly show Manley quarry but at that date, the quarry on Simmonds Hill was not marked. There is a sketch of Simon’s Hill (now Simmonds Hill) but no quarry is shown and the area is simply labelled ‘Commons’. In contrast, Manley Quarry is sketched showing the workings and buildings.

But - what was the windmill used for shown next to ‘Croft by the house – tenant Alice Frodsham’? The ‘Moss’ has clear sketch markings but which are hard to interpret –possibly peat cutting? The spelling of many places varies, such as Molesworth Common (now Moldsworth) and the Forest of Dalamere (not Delamere). Lords Well is documented but not Swans Well which was an important landmark on a map of Delamere Forest dated 1813.

As usual with historical research the documents throw up as many questions as answers!

The project has now published its findings online and in a booklet.

“A tin case containing some old plans of lands seemingly of no use” reads the faded, discoloured, remnant of the original wrapper inside Cheshire Record Office folder D8835. How wrong this was.

The staff at the Record Office had kindly directed us to this treasure and it provides a fascinating insight into the Manor of Manley. The accession contains four maps of Manley. The separate sections are marked north, south, east and west quarters and include instructions how to overlap them to make the complete manor. The heading of the maps is “A Plan of the Manor of Manley belonging to Jocelyn Deane Esq 1777 taken from an original plan for Robert Davies Esq 1722.”

We have been researching Manley as part of the Sandstone Ridge Trust ‘The Ridge Rocks and Springs’ project funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund. The project is looking at quarries, ancient water supplies and historic graffiti along Cheshire’s sandstone ridge.

Previous research suggests that Manley quarry has been in use since Roman times but there are two main quarries in the parish and it is often difficult to distinguish between them when reference is being made to ‘the quarry’. One is usually known as Manley Quarry, and the other one is on Simmonds Hill. These maps clearly show Manley quarry but at that date, the quarry on Simmonds Hill was not marked. There is a sketch of Simon’s Hill (now Simmonds Hill) but no quarry is shown and the area is simply labelled ‘Commons’. In contrast, Manley Quarry is sketched showing the workings and buildings.

But - what was the windmill used for shown next to ‘Croft by the house – tenant Alice Frodsham’? The ‘Moss’ has clear sketch markings but which are hard to interpret –possibly peat cutting? The spelling of many places varies, such as Molesworth Common (now Moldsworth) and the Forest of Dalamere (not Delamere). Lords Well is documented but not Swans Well which was an important landmark on a map of Delamere Forest dated 1813.

As usual with historical research the documents throw up as many questions as answers!

The project has now published its findings online and in a booklet.

Thursday, 5 October 2017

Medieval Deeds Project

Searching the word ‘deed’ on our online catalogue brings up over 1500 results. Each of these results could relate to a single item or to an entire collection of numerous boxes.

Due to the vast amount of deeds we have, we decided to make them more readily accessible to researchers. The plan was to digitise the deeds and improve the description of them, with the resulting output then added to our catalogue. Catalogue searches would be more effective and show up more detailed results. The catalogue could direct users to exactly the right deed and also provide a digital image of it- perfect for people who can’t make it into the search room. Having the deeds digitised also reduces the need to produce the original, and reduces the handling of these items when in a number of cases a digital surrogate is enough.

The plan was to digitise the deeds and improve the description of them.

The decision was taken to start the process with our Medieval Deeds. These are mostly written in Latin, so extracting key pieces of information from them would be of most benefit to the average user with little to no knowledge of the language.

Due to the specialist knowledge needed to read and understand Latin and the writing style (palaeography) we decided to seek out people with this skill. To enable as broad an array of people as possible to help us with this, we decided to use a digital platform, from which we created a digital collaboration project. A fully digital project allows people to volunteer from their own home and in their own time.

After some research, we chose Trello to build our project on. Trello is a free online tool designed to assist collaborative working; assigning members of the team different tasks which can be seen by all. It allows multiple people to log in simultaneously from wherever they are. The layout is similar to a Kanban board, where you move items to the right as they progress through the workflow (far left is items pending, far right is items completed). This fit in well with our plan for the project.

|

| Current screenshot from the project. |

If you want to see this platform in action please watch our YouTube video. We are still relatively early on in this process and looking for more volunteers to help to push it forward.

The particular deeds in this project are characterised by the fact that they are made of parchment (stretched and scraped animal skins) and display a variety of seals and seal attaching techniques. They are primarily written in iron gall ink. The longevity of parchment documents means that they survive today in remarkable condition however extra care needs to be taken with the sometimes brittle and fragmented wax seals.

|

| Close-up of one of the seals from the DCH Collection. |

The Medieval Deeds digitised for this project are taken from our DCH collection, “Title deeds and leases, Cheshire and elsewhere, 12th century - c1900”, specifically DCH/J- Deeds relating to various Townships.

Before digitising, any folded deeds were flattened and restored where necessary by our in-house conservation department. We have now digitised around 500 of the Medieval Deeds in our collection.

Currently, all these deed images are uploaded to Trello and our volunteers can choose from them and allocate one to themselves. The volunteer then translates the key sections of the deed and moves it onto the next stage. We don’t ask for a full transcription- just for essential information to be extracted and translated into English. This mainly consists of names, dates and locations but also costs involved and relationships between named people.

At this point, a different volunteer takes over and quality checks the description and adds their comments if required. The information is then checked a further time before being passed over to our in-house Latin specialist for final verification. When a batch of deeds has been completed, we will upload the images and results of the project onto our catalogue. This will be done intermittently until all deeds are finalised.

If you have a thorough understanding of Latin and feel that you could help us, please get in touch for more information at recordoffice@cheshiresharedservices.gov.uk

All you require is an email address; computer and internet access to get started. Some of our volunteers even visit their local library to get internet access and assist us! All work is undertaken at a time and place convenient to you. There is no minimum number of hours required to help out.

In time, this will make the whole of DCH/J easier to search and increase the value and knowledge which can be gained from these manuscripts.

Want to know more about this project? See more:

On YouTube:

Discovering Deeds Playlist

Discovering Deeds Playlist

On our blog:

Deeds Indeed

Deeds Indeed

Thursday, 10 August 2017

Cheshire’s Only Island

Did anyone see a lovely little piece on Springwatch earlier this year where documentary cameraman James Bayliss-Smith took off to Hilbre Island as a homage to his grandfather who took many bird photographs there, especially of wading birds stopping off on their way to their breeding grounds? It got me wondering what we might hold here in the Archives relating to “Cheshire’s only Island”. A quick search of the catalogue actually reveals 155 items listed under “Hilbre”.

If you don’t know of Hilbre, it (and its two smaller companions Middle Eye – sometimes, confusingly, Little Hilbre - and Little Eye) is “an archipelago consisting of three islands at the mouth of the estuary of the River Dee, the border between England and Wales at this point. The islands are administratively part of the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral." At low tide the islands can be reached on foot from West Kirby. An image from the Ordnance Survey 1st Edition 25 inch (Sheet XII-6) from 1871 shows Hilbre Island Telegraph Station and the ‘Submarine telegraph’ line to the mainland

One of the earliest documents we hold that mentions Hilbre is a copy (but an early one) of a seventeenth century Indenture (ref: EDD 13/5/1)

In the same book, I then spotted a 17 page chapter entitled “A year on hilbre” which is written by an Ann Cleeves about her and her husband Tim’s first year on Hilbre (1977-78) where he was employed as the resident Warden. In the list of Contributors printed on the dust jacket it states: “A. CLEEVES, wife of the Warden lived on Hilbre from 1977 to 1981, and holds a Certificate of Qualification in Social Work, University of Liverpool.” This raised my eyebrows a little, and some judicious googling later revealed that this was indeed the well-known crime writer, best known for her Vera Stanhope and Shetland Island series of titles. In several interviews Ann has alluded to this period, and indeed on her own biography she writes “Soon after they married, Tim was appointed as warden of Hilbre, a tiny tidal island nature reserve in the Dee Estuary. They were the only residents, there was no mains electricity or water and access to the mainland was at low tide across the shore. If a person's not heavily into birds - and Ann isn't - there's not much to do on Hilbre and that was when she started writing.” However, to the best of my knowledge, Ann has not actively publicised this early work before. As this actually appears to be her very first published work, it remains to be seen whether this now leads to a rush of collectors suddenly vying for what must be a somewhat limited number of copies. Time will tell!

As always there appears to be something for everyone here at Cheshire Archives – from seventeenth century Indentures to the first tentative steps towards literary stardom. All that is left (apart from the other 150-odd related items on the catalogue) is to actually visit the Islands themselves, something that a combination of the tide and the weather forecast has so far combined to stop me undertaking . I shall have to remedy that. Which brings me to my final, and very important, point to note if you are going to visit Hilbre – you really do need to plan your visit very carefully around the tide timetables. An excellent guide with very precise instructions on when you can and cannot go, and on what route to take across the sands, can be found here http://www.deeestuary.co.uk/hilbre/plan.htm. The tide timetables themselves can be found in many places including on the BBC website http://www.bbc.co.uk/weather/coast_and_sea/tide_tables/5/461#tide-details

(Addendum: Since I wrote this, I’ve been doing some work on the population of Hilbre at census time which shows some fascinating glimpses into the history of the island in the second half of the nineteenth and first years of the twentieth centuries. At times, it was home to a surprising number of people. You’ll have to await a future blog to read about this in full.)

If you don’t know of Hilbre, it (and its two smaller companions Middle Eye – sometimes, confusingly, Little Hilbre - and Little Eye) is “an archipelago consisting of three islands at the mouth of the estuary of the River Dee, the border between England and Wales at this point. The islands are administratively part of the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral." At low tide the islands can be reached on foot from West Kirby. An image from the Ordnance Survey 1st Edition 25 inch (Sheet XII-6) from 1871 shows Hilbre Island Telegraph Station and the ‘Submarine telegraph’ line to the mainland

|

| 1871 OS map |

|

| EDD 13/5/1 |

There are also many Local Studies items. These include a large range of articles in Cheshire Life, a full run of which is housed on open access in the searchroom. Many of these are by Norman Ellison, who wrote A Naturalist’s Notebook in the magazine and was clearly a huge fan of Hilbre. One of his pieces from Cheshire Life in April 1970 is an interesting article entitled “Storm over Hilbre” with an excellent and rather emotive image included. Another book that interested me when I found it is Atgofion Ynyswr (roughly “Memoirs of an Islander”) by Lewis Jones, Hilbre gynt (formerly of Hilbre) published in Liverpool in Welsh, although there are some specific related pieces included in English (ref: 228560). Mr Jones was the Telegraph Station Keeper on Hilbre (at the location on the map above) from 1888 until his retirement (back to Wales hence, I’m guessing, the language of the book) in 1923. The book looks absolutely fascinating, but is rather lost on me due to its language of publication. Thankfully I can see online that a Hugh Begley undertook a translation in 2003, although this has not, unfortunately, been published. It is, however, available to consult at West Kirby Library.

Things then took a slightly unexpected turn when I found a fantastic book called Hilbre, The Cheshire Island: its history and natural history (ref: 016561) published in 1982. This lovely 306pp volume is notable for a number of reasons. Firstly, its cover and several internal illustrations were undertaken by a Guernsey born prize winning artist, Laurel Tucker who won many prizes and huge acclaim for her work, particularly with regard to her bird illustrations. Very sadly she died in 1986, aged only 35.

In the same book, I then spotted a 17 page chapter entitled “A year on hilbre” which is written by an Ann Cleeves about her and her husband Tim’s first year on Hilbre (1977-78) where he was employed as the resident Warden. In the list of Contributors printed on the dust jacket it states: “A. CLEEVES, wife of the Warden lived on Hilbre from 1977 to 1981, and holds a Certificate of Qualification in Social Work, University of Liverpool.” This raised my eyebrows a little, and some judicious googling later revealed that this was indeed the well-known crime writer, best known for her Vera Stanhope and Shetland Island series of titles. In several interviews Ann has alluded to this period, and indeed on her own biography she writes “Soon after they married, Tim was appointed as warden of Hilbre, a tiny tidal island nature reserve in the Dee Estuary. They were the only residents, there was no mains electricity or water and access to the mainland was at low tide across the shore. If a person's not heavily into birds - and Ann isn't - there's not much to do on Hilbre and that was when she started writing.” However, to the best of my knowledge, Ann has not actively publicised this early work before. As this actually appears to be her very first published work, it remains to be seen whether this now leads to a rush of collectors suddenly vying for what must be a somewhat limited number of copies. Time will tell!

As always there appears to be something for everyone here at Cheshire Archives – from seventeenth century Indentures to the first tentative steps towards literary stardom. All that is left (apart from the other 150-odd related items on the catalogue) is to actually visit the Islands themselves, something that a combination of the tide and the weather forecast has so far combined to stop me undertaking . I shall have to remedy that. Which brings me to my final, and very important, point to note if you are going to visit Hilbre – you really do need to plan your visit very carefully around the tide timetables. An excellent guide with very precise instructions on when you can and cannot go, and on what route to take across the sands, can be found here http://www.deeestuary.co.uk/hilbre/plan.htm. The tide timetables themselves can be found in many places including on the BBC website http://www.bbc.co.uk/weather/coast_and_sea/tide_tables/5/461#tide-details

(Addendum: Since I wrote this, I’ve been doing some work on the population of Hilbre at census time which shows some fascinating glimpses into the history of the island in the second half of the nineteenth and first years of the twentieth centuries. At times, it was home to a surprising number of people. You’ll have to await a future blog to read about this in full.)

Labels:

Ann Cleves,

archives,

birds,

Cheshire Archives and Local Studies,

Cheshire Life,

estuary,

Hilbre,

indenture,

island,

Little Eye,

Middle Eye,

naturalist,

ordnance survey,

River Dee,

telegraph station

Friday, 16 June 2017

Protecting Cityscapes

This year we celebrate 50 years of the Civic Amenities Act 1967, and what it means for our historic places across England, Wales and Scotland. President of The Civic Trust and MP, Lord Duncan Sandys helped to bring this legislation into being. The Act was passed in 1967 but a number of events leading up to it pushed conservation to the forefront.

Many recommendations in the report were used as the basis for future changes, but lack of funding meant that redevelopment was slow and ineffective in reaching the goals over the short term. But it was the beginning.

1960s

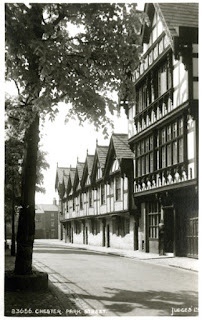

In the 1950-60s there was concern that the historical face of Chester was being slowly obliterated which sparked the creation of Chester Civic Trust in January 1960. After their formation, the Chester Civic Trust immediately had to step in regarding The Blue Bell. The Blue Bell in Northgate Street was in danger of being demolished, but the Chester Civic Trust put forward their case that it should be kept and restored. The council agreed to keep the building and to fund the restoration project themselves. This was one of the first major wins for the Trust.

Around this time, lots of new development projects were being proposed. This included small and larger tower blocks. Chester Civic Trust tried to fight to stop these going ahead. Those approved with only minor consideration for the views of the public included Commerce House (now demolished to make way for Storyhouse); The Police Headquarters (now demolished to make way for the ABode hotel and Chester West and Chester council HQ) and the replacement for Clemences restaurant on Northgate Street.

Chester Civic Trust did however make some headway and advised the council not to demolish a number of historically important houses on Queen Street and to acquire and renovate the Nine houses on Park Street, which still stand today. The idea of preserving and conserving buildings had been brought to the forefront of people’s minds.

1967

1967 brought the Civic Amenities Act. The Act required local authorities to start to recognise groups of buildings with historical value and designate them as conservation areas. Most of the centre of the city was designated. Previously, historical buildings were at risk of becoming derelict and demolished with little money or support to stop this. The aim of the Act was to conserve groups of buildings which made a town, city or village unique and ensure their value was not overshadowed by new developments.

In the new conservation areas, additions to properties such as extensions were regulated and trees within the areas were occasionally granted historical importance and not allowed to be felled. Also, any “proposed developments must preserve or enhance the special architectural or historic character of the conservation area. This does not specifically exclude innovative proposals but they must be sympathetic to their context.”

Out of this Act came four Historic Town Reports (one each for Bath, Chester, Chichester and York). Chester commissioned their Historic Town Report to be undertaken by Donald Insall Associates entitled ‘Chester, A study in Conservation’.

More recently, conservation work was undertaken on the City Walls in 2013 and on Eastgate and Eastgate Clock in 2014. Modernisation and conservation of buildings around Chester Station has also been undertaken after some had fallen into disrepair. The Civic Amenities Act 1967 has made a difference to the cityscape of current Chester with the spirit of conservation continuing on.

More photographs from the Insall Collection will be shown on our Twitter page @CheshireRO for #civicday 17th June 2017. The whole collection of images taken for Chester’s Historic Town Report are held by Cheshire Archives and Local Studies and we are working to make them accessible to the public as soon as possible.

1945

After the war there was a need to rebuild war damaged areas across the country. Chester had been largely unaffected by the architectural damages of war but was in need of an overhaul to rectify some of its problems. A Plan for Redevelopment was written up by Charles Greenwood in 1945. It focused on controlling the city centre traffic and dealing with old housing with undesirable living conditions. About 2500 houses over 100 years old were condemned.

After the war there was a need to rebuild war damaged areas across the country. Chester had been largely unaffected by the architectural damages of war but was in need of an overhaul to rectify some of its problems. A Plan for Redevelopment was written up by Charles Greenwood in 1945. It focused on controlling the city centre traffic and dealing with old housing with undesirable living conditions. About 2500 houses over 100 years old were condemned.

|

| Chester, Francis Street. Image Courtesy of Chester History & Heritage. Image Bank ch5860 |

Many recommendations in the report were used as the basis for future changes, but lack of funding meant that redevelopment was slow and ineffective in reaching the goals over the short term. But it was the beginning.

1960s

In the 1950-60s there was concern that the historical face of Chester was being slowly obliterated which sparked the creation of Chester Civic Trust in January 1960. After their formation, the Chester Civic Trust immediately had to step in regarding The Blue Bell. The Blue Bell in Northgate Street was in danger of being demolished, but the Chester Civic Trust put forward their case that it should be kept and restored. The council agreed to keep the building and to fund the restoration project themselves. This was one of the first major wins for the Trust.

Around this time, lots of new development projects were being proposed. This included small and larger tower blocks. Chester Civic Trust tried to fight to stop these going ahead. Those approved with only minor consideration for the views of the public included Commerce House (now demolished to make way for Storyhouse); The Police Headquarters (now demolished to make way for the ABode hotel and Chester West and Chester council HQ) and the replacement for Clemences restaurant on Northgate Street.

Chester Civic Trust did however make some headway and advised the council not to demolish a number of historically important houses on Queen Street and to acquire and renovate the Nine houses on Park Street, which still stand today. The idea of preserving and conserving buildings had been brought to the forefront of people’s minds.

|

| Chester: Park Street View of the Nine Houses. Image Bank c10324 |

1967 brought the Civic Amenities Act. The Act required local authorities to start to recognise groups of buildings with historical value and designate them as conservation areas. Most of the centre of the city was designated. Previously, historical buildings were at risk of becoming derelict and demolished with little money or support to stop this. The aim of the Act was to conserve groups of buildings which made a town, city or village unique and ensure their value was not overshadowed by new developments.

In the new conservation areas, additions to properties such as extensions were regulated and trees within the areas were occasionally granted historical importance and not allowed to be felled. Also, any “proposed developments must preserve or enhance the special architectural or historic character of the conservation area. This does not specifically exclude innovative proposals but they must be sympathetic to their context.”

Out of this Act came four Historic Town Reports (one each for Bath, Chester, Chichester and York). Chester commissioned their Historic Town Report to be undertaken by Donald Insall Associates entitled ‘Chester, A study in Conservation’.

|

Cover of Donald Insall’s report “Chester: A Study in Conservation.” Taken from the Insall Collection at Cheshire Archives and Local Studies. |

Sir Donald Insall and his team identified key streets and areas in need of conservation efforts. Photographs were taken, voice recordings of initial impressions made and rough conservation costs drawn up of properties at risk. The photographs produced for this work are now held on-site at Cheshire Archives and Local Studies.

The report considered the most problematic area to be Bridgegate. A base of operations was set up in the area, and the need for swift restoration was highlighted when the office’s roof collapsed!

Gamul House and Gamul Place were some of the first chosen to be preserved and extensive work was carried out in this area and the rest of Bridgegate. A short film ‘The Conservation Game’ was produced and shown on television to highlight the considerations over this period and to follow the renovations of the buildings.

The report considered the most problematic area to be Bridgegate. A base of operations was set up in the area, and the need for swift restoration was highlighted when the office’s roof collapsed!

Gamul House and Gamul Place were some of the first chosen to be preserved and extensive work was carried out in this area and the rest of Bridgegate. A short film ‘The Conservation Game’ was produced and shown on television to highlight the considerations over this period and to follow the renovations of the buildings.

|

| Gamul House, Lower Bridge Street, Chester : following restoration |

|

| Houses in Shipgate Street, Chester before restoration |

|

| Houses in Shipgate Street, Chester following restoration. Taken from the Insall Collection at Cheshire Archives and Local Studies. |

More recently, conservation work was undertaken on the City Walls in 2013 and on Eastgate and Eastgate Clock in 2014. Modernisation and conservation of buildings around Chester Station has also been undertaken after some had fallen into disrepair. The Civic Amenities Act 1967 has made a difference to the cityscape of current Chester with the spirit of conservation continuing on.

More photographs from the Insall Collection will be shown on our Twitter page @CheshireRO for #civicday 17th June 2017. The whole collection of images taken for Chester’s Historic Town Report are held by Cheshire Archives and Local Studies and we are working to make them accessible to the public as soon as possible.

Wednesday, 14 June 2017

Monumental Inscriptions

A few months ago, whilst I was producing documents for customers in the searchroom, a customer ordered D5104 which the catalogue describes, accurately but somewhat drily, as “1 folder: Transcripts of monumental inscriptions made from tombs and printed sources, various Cheshire parishes, 17c-20c”

When I found the folder and opened it to check its contents it looked like hundreds of tiny typed copies of inscriptions in small bundles, each one held together by a paper clip. Unsurprisingly, not all the paper clips were still in the right place. Using the description and numbers of items in each theme from the full paper catalogue that the customer had seen here http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/browse/r/h/8005a51f-0e4c-4234-a3a4-361fd9eed21d it didn't take long to make sense of the jumbled slips, and present the customer with what she expected. To prevent this happening again and to make the experience of reading them a little less chaotic in future, we decided to copy the slips onto A4 sheets by theme, which gave us the chance to experience a little flavour of what lay within!

We’ll start with the benevolent Joseph Bleamire, Coachman, 1760 (buried in Barthomley):

Then, how about the somewhat productive Sir Henry Bunbury (17th Century, from Thornton-le-Moors):

And the even more eye watering Lady Katherine Clegg from Heswall:

Next how about poor Latitia Leyland, Born and Died October 1st 1837 in Cheadle:

If you’ve managed to compose yourself again after reading that one, we can return to issues of mind boggling productivity with Ann Barker of Middlewich:

Secondly, here is poor William Pownall of Mobberley who died in 1864, aged 20:

A note is added stating “He was born at Mosley Common in Lancashire. He claimed that he drank a gallon of malt liquor every day for sixty years”. Five other centenarians are also recorded, although, sadly perhaps, their level of alcohol consumption isn’t.

If you are interested in Monumental Inscriptions in a more structured sense then please note that a search on our catalogue for that term lists over 400 items in total. Please also be aware that we have a large collection of individual volumes on open access in the public searchroom that each relate to a different Parish in the County.

When I found the folder and opened it to check its contents it looked like hundreds of tiny typed copies of inscriptions in small bundles, each one held together by a paper clip. Unsurprisingly, not all the paper clips were still in the right place. Using the description and numbers of items in each theme from the full paper catalogue that the customer had seen here http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/browse/r/h/8005a51f-0e4c-4234-a3a4-361fd9eed21d it didn't take long to make sense of the jumbled slips, and present the customer with what she expected. To prevent this happening again and to make the experience of reading them a little less chaotic in future, we decided to copy the slips onto A4 sheets by theme, which gave us the chance to experience a little flavour of what lay within!

We’ll start with the benevolent Joseph Bleamire, Coachman, 1760 (buried in Barthomley):

Coachman to/JOHN CREWE Esq./left by his last Will and /Testament

the Sum of Sixty/Pounds the Interest of which/to be laid out

weekly in brown/Bread of the value of two/Pence per Loaf and to

be/distributed in the Parish Church of Barthomley/

every/ Sunday immediately after/morning Service to the Poor/of

the Township of Crewe.

Then, how about the somewhat productive Sir Henry Bunbury (17th Century, from Thornton-le-Moors):

He married two Wives: first Anne/by whom he had yssue 3 sonnes

And 6 daughters/and Martha by whom he had/yssue 7 sonnes and 3

daughters.

And the even more eye watering Lady Katherine Clegg from Heswall:

She was married on the 22nd July 1650 and died on the 26th

August 1666 aged 39. She bore 15 children, 13 sons and two

daughters.

Next how about poor Latitia Leyland, Born and Died October 1st 1837 in Cheadle:

Sweet Babe, she glanc’d into our world to see

A sample of our misery,

Then turn’d away her languid eye,

To drop a tear or two and die

The cup of life to her lips she press’d

Found the taste bitter and refus’d the rest.

Sweet Babe no more but Seraph now

Before the shrine behold her bow,

Adore the grace that brought her there

Without a wish – without a care,

That wash’d her soul in Calvary’s stream

That shorten’d life’s distressing dream.

Short pain – short grief – dear Babe was thine

Now joys eternal and divine.

If you’ve managed to compose yourself again after reading that one, we can return to issues of mind boggling productivity with Ann Barker of Middlewich:

Here lies Ann, Wife of Daniel

Barker, who died July 3, 1778,

Aged 77

Some have children and some have none,

But here lies the Mother of Twenty one

Time for reflection in Church Lawton where “it is said that an iron tombstone by the main gate of the churchyard bore the following inscription (long since illegible)”:

He was a brute of a husband and

led me a shocking life

Another desperately dispiriting pair now, firstly Martha Clark of Bidston who died in 1846, aged 21:

Nineteen years/a Maid/Two years a Wife./Nine days/a Mother/And

then /Departed Life.

Secondly, here is poor William Pownall of Mobberley who died in 1864, aged 20:

All you that stop this Stone to seeMore happily, it is pleasing to discover that some lived just a little longer. Joseph Watson, ‘Park-keeper’ died in 1753, aged 104 and is buried in Disley:

Pray think how sudden death took me

I in my youth God call’d away

Just before my wedding day

He was Park Keeper to Mr Peter Leigh, at Lyme,

more than 64 years and was ye first

that Perfected the Art of Driving ye Stags.

Here lyeth also the body of Elizabeth his wife,

aged 94 years, to whom

he had been married 75 years.

Reader, take notice, the longest life is short.

A note is added stating “He was born at Mosley Common in Lancashire. He claimed that he drank a gallon of malt liquor every day for sixty years”. Five other centenarians are also recorded, although, sadly perhaps, their level of alcohol consumption isn’t.

If you are interested in Monumental Inscriptions in a more structured sense then please note that a search on our catalogue for that term lists over 400 items in total. Please also be aware that we have a large collection of individual volumes on open access in the public searchroom that each relate to a different Parish in the County.

Labels:

ancestry,

archive,

archives,

barthomley,

burial,

Cheadle,

Cheshire,

Cheshire Archives and Local Studies,

Disley,

Family History,

Heswall,

Middlewich,

Mobberley,

monumental inscription,

parish,

Thornton-le-Moors

Friday, 9 June 2017

A honeymoon tour to remember!

Who has kept a diary? I have – with a birthday at Christmas time and growing up in the seventies there was every chance I would receive at least one diary, usually with matching pen, every year – but even the most attractive of them (purple velvet) still didn’t inspire me much beyond February. Then there were the teenage years ... And the last diary I kept? Recording a trip to Japan in my early twenties I supposed I wouldn’t make again.

The wonderful thing about diaries in Cheshire's archive collections is that we can recognise all of this and ourselves in them. For International Archives Day 2017 and #archivestourism here are extracts from a young woman's honeymoon diary.

Wednesday July 13th 1892

We were to travel by a train which left Alderley Edge soon after half past three in the afternoon – Leo and I. The express which Leo had decided on to take us up to London would not stop for us at Alderley, though most politely requested to do so; but brides and bridegrooms were things it was very accustomed to, and its iron heart was not to be moved. The express left Manchester at a quarter past four, so we had a good half hour to wait at Crewe. Leo put me in the waiting room to rest before the journey. He came to summon me presently, and took me to the express which had come in, and finding his name on the window of a coupe, he opened the door. We reached Euston about half past eight. Leo got a cab and we packed in with our luggage, my box and Leo’s portmanteau and he had a hat box, and I a handbag, and set off for the Victoria Hotel in Northumberland Avenue. We were expected, and our room was waiting for us. It is a very fine hotel, the largest I have yet been in.

Thursday July 14th

I am ashamed to say what time it was when we got up, but Leo had slept badly, having had toothache, which was very unromantic, but true nevertheless.

We went down to breakfast (I might say at last), and Leo ordered coffee, and fried soles, and toast, which was very nice, but the room was as close as ever, and my new morning frock pinched so dreadfully round the neck, that I unhooked it, and furtively fastened the brooch in again over a good gap of collar. (Otherwise, it is a very nice blue serge, and in my heart I rather admire it, with collar and cuffs.)

So Leo proposed that we should go and see ‘Venice’ at Olympia, as a good lazy way of passing the time, for as we know that there were canals and gondolas, we naturally thought that they must be in gardens. In other respects, we knew nothing at all about it.

The gardens were creations of our own wild imagination … the glass-making was in progress at certain hours, but we did not see it …. We went to see the – I know not what to call it – say, spectacle. Presently the play began, a hash-up of all sorts of things, the whole thing was sung; and we were too far away to hear anything of words.

We did not want any supper, after the long dinner we had had, but I was very anxious to be allowed to pass the night on the saloon couches; the cabins looked so full and close, and I don’t care to be sick before strangers, in a box. At first we were told that I could and Leo went away cheerfully to look after his own berth. But by and by came the stewardess to me, and said that it could only be allowed if all the berths were taken up. When Leo came back he had found a berth, and an old lacrosse acquaintance. I waited awhile, but I was doomed to disappointment; the stewardess came and bore me off to a berth, in a cabin containing four. The whole place was about as big as a very small dining table and it already contained three Americans. I climbed into my top berth, half undressed and lay down. Presently came the stewardess and dealt out basins. ‘Prevention is better than cure’ she said with a pleasing smile. My heart sank right to the bottom end of my berth. The abominable Adelaide began to roll almost immediately after leaving Harwich, and one of the Americans succumbed early, and kept it up all night. If this were any consolation to me I had the pleasure of lying and listening to it, until the small hours, when I too succumbed.

Friday July 15th

Not to have slept till morning, and not much then, does not conduce to general briskness, to say nothing of the horrors of seasickness and a close cabin. Soon after six I roused up altogether, for the stewardess came in and said that we were later than usual, for we had had a very rough passage. And that was Leo’s calm night.

Frances Crompton was born near Prestbury in 1866, and lived in Wilmslow, where she met and married bank manager John Leopold Walsh. They later lived in Holmes Chapel and Chelford. She published 29 children’s stories, was a skilled painter and kept her Gardening Diary begun in 1915. She died in 1952 and her daughter deposited her diaries in the archives. The collection reference is D 5453.

With thanks to volunteer Hilary Morris for transcribing diary extracts.

The wonderful thing about diaries in Cheshire's archive collections is that we can recognise all of this and ourselves in them. For International Archives Day 2017 and #archivestourism here are extracts from a young woman's honeymoon diary.

Wednesday July 13th 1892

We were to travel by a train which left Alderley Edge soon after half past three in the afternoon – Leo and I. The express which Leo had decided on to take us up to London would not stop for us at Alderley, though most politely requested to do so; but brides and bridegrooms were things it was very accustomed to, and its iron heart was not to be moved. The express left Manchester at a quarter past four, so we had a good half hour to wait at Crewe. Leo put me in the waiting room to rest before the journey. He came to summon me presently, and took me to the express which had come in, and finding his name on the window of a coupe, he opened the door. We reached Euston about half past eight. Leo got a cab and we packed in with our luggage, my box and Leo’s portmanteau and he had a hat box, and I a handbag, and set off for the Victoria Hotel in Northumberland Avenue. We were expected, and our room was waiting for us. It is a very fine hotel, the largest I have yet been in.

Of course we were much too late for dinner, and we were too tired to care for a private one, so Leo ordered cutlets and tea, as the most refreshing things he could think of, to be ready immediately. Leo, who knew the hotel, made his way to the coffee room, where our tea was to be laid, a handsome room, but oh so hot and close! Our tea came soon, cutlets, chip potatoes, tea and toast, and very good and refreshing it was, but I was not sorry to leave the hot room as soon as possible, and as we were both very tired, we went straight away to bed. I do not seem to have much to say about today, but it is not a day one would choose to write about.

Thursday July 14th

I am ashamed to say what time it was when we got up, but Leo had slept badly, having had toothache, which was very unromantic, but true nevertheless.

We went down to breakfast (I might say at last), and Leo ordered coffee, and fried soles, and toast, which was very nice, but the room was as close as ever, and my new morning frock pinched so dreadfully round the neck, that I unhooked it, and furtively fastened the brooch in again over a good gap of collar. (Otherwise, it is a very nice blue serge, and in my heart I rather admire it, with collar and cuffs.)

Our newly weds have the best part of a day to kill before their train to the coast and the boat for Rotterdam. They would both have liked Kew (Frances will become an expert gardener) but it’s too far out and museums or galleries seem like hard work …

So Leo proposed that we should go and see ‘Venice’ at Olympia, as a good lazy way of passing the time, for as we know that there were canals and gondolas, we naturally thought that they must be in gardens. In other respects, we knew nothing at all about it.

The gardens were creations of our own wild imagination … the glass-making was in progress at certain hours, but we did not see it …. We went to see the – I know not what to call it – say, spectacle. Presently the play began, a hash-up of all sorts of things, the whole thing was sung; and we were too far away to hear anything of words.

And on to the boat at Harwich, and perhaps the reasons for Frances’ growing dissatisfaction becomes clear … Leo predicts a calm night …

We did not want any supper, after the long dinner we had had, but I was very anxious to be allowed to pass the night on the saloon couches; the cabins looked so full and close, and I don’t care to be sick before strangers, in a box. At first we were told that I could and Leo went away cheerfully to look after his own berth. But by and by came the stewardess to me, and said that it could only be allowed if all the berths were taken up. When Leo came back he had found a berth, and an old lacrosse acquaintance. I waited awhile, but I was doomed to disappointment; the stewardess came and bore me off to a berth, in a cabin containing four. The whole place was about as big as a very small dining table and it already contained three Americans. I climbed into my top berth, half undressed and lay down. Presently came the stewardess and dealt out basins. ‘Prevention is better than cure’ she said with a pleasing smile. My heart sank right to the bottom end of my berth. The abominable Adelaide began to roll almost immediately after leaving Harwich, and one of the Americans succumbed early, and kept it up all night. If this were any consolation to me I had the pleasure of lying and listening to it, until the small hours, when I too succumbed.

Friday July 15th

Not to have slept till morning, and not much then, does not conduce to general briskness, to say nothing of the horrors of seasickness and a close cabin. Soon after six I roused up altogether, for the stewardess came in and said that we were later than usual, for we had had a very rough passage. And that was Leo’s calm night.

Frances Crompton was born near Prestbury in 1866, and lived in Wilmslow, where she met and married bank manager John Leopold Walsh. They later lived in Holmes Chapel and Chelford. She published 29 children’s stories, was a skilled painter and kept her Gardening Diary begun in 1915. She died in 1952 and her daughter deposited her diaries in the archives. The collection reference is D 5453.

With thanks to volunteer Hilary Morris for transcribing diary extracts.

Friday, 19 May 2017

Votes for Women!

Over the weekend of 20th and 21st May, Chester will play host to their very own Women of the World (WOW) Festival. Based at Storyhouse, WOW will feature a line-up of talks, performances, panel discussions and workshops dedicated to celebrating women and girls worldwide. The festival hopes to bring women and men together to examine the obstacles still faced today and how they can be overcome.Thanks to WOW, I was intrigued to delve into Chester’s past to discover how women of Chester have strived to make the world a fairer, more equal place.

Little is known about Chester’s connection to the ‘Votes for Women’ movement, however the discovery of an article written in 1939 to celebrate the 21st anniversary of women’s enfranchisement, sheds considerable light on the activities and organisations in Chester dedicated to achieving votes for women.

This sparked an idea! Given that newspapers were the principle means of communicating to a mass audience and the most widespread media form in the Edwardian age, I wondered whether it would be possible to piece together Chester’s suffrage past using old editions of local newspapers held on microfilm at the Record Office.I discovered a number of local newspaper reports detailing the peaceful activities of organisations that had set up branches in Chester, particularly the Chester Women’s Suffrage Society, the Women’s Freedom League and the National Union of Women’s Suffragist Societies (NUWSS). An article written by a ‘Lady Correspondent’ remarks that all branches of the NUWSS, including the Chester branch, stood for the ‘enfranchisement of women worked for on peaceful and law-abiding lines, and that the recourse to violence is destructive.’ (Chester Chronicle, 18th July 1914, MF 204/38).Unlike more militant organisations such as the Women’s Social and Political Union, evidence suggests that organisations in Chester concentrated on legal and peaceful means of drawing attention to their cause by arranging speeches, events and the sale of merchandise to raise funds. The Women’s Freedom League even opened a Suffrage shop at 45 St. Werburgh’s Street where they sold merchandise such as badges.

Despite the preference for legal and peaceful means of protest in Chester, Emmeline Pankhurst, founder of the more militant WSPU, visited the city in January 1912. Despite the Hall not being filled, reports indicate that Mrs. Pankhurst received a ‘good reception’. Speaking with ‘great clearness and… putting her points with telling effect’, Mrs. Pankhurst declared that she wanted ‘every human being, if possible, to have some control over the spending of taxation and the making of laws’. Mrs. Pankhurst also spent time defending militancy commenting that ‘it was not the reasonable patient person who ever got anything’ and posing the question ‘Were the women of Chester prepared to help?’

The article I first found in the Cheshire Observer dated 1939 reveals that there was one particular incident that saw the events in Chester make widespread national news.

A report from the Cheshire Observer dated July 27th 1912 harked at the ‘Exciting and alarming incident’, describing how the ‘excited lady’ appeared to ‘rush out of the crowd and hurl something at the car’.

Reporting on the aftermath of ‘The Chester Incident’, the Cheshire Observer recounted events at the Police Court. Charged with the assault of Frank Clark who had been driving the car that was hit by flour, the assailant was identified as Mary Phillips, a journalist from Cornwall. Giving evidence, the Chief Constable asked ‘the Bench to make an example of the defendant.’ (Cheshire Observer, 27th July 1912 MF 225/35)

‘There was no doubt that the missile was intended for the Prime Minster. If Cabinet Ministers could not travel about the country without attempts being made to assault them, then the country must be coming to state of anarchy.’ (Cheshire Observer, 27th July 1912, MF 225/35). Despite denying the charge of assault and protesting that if she had intended to injure the Prime Minister or damage the car she would have used a more dangerous missile, Mary Phillips was found guilty. She had the choice to pay 5s. in fines and additional costs, or receive seven days imprisonment in the second division. She refused to pay the fine, but it was later paid by a ‘prominent Chester Liberal’ whose identity remains unknown still.

By piecing together the newspaper articles above, we can come to understand that the women of Chester were engaged with the political campaign to give women the vote and furthermore, that the streets of Chester did witness militant action to advance this aim. 2018 marks 100 years since the Representation of the People Act 1918 gave the vote to around 8.4 million women over the age of 30 who met certain conditions, including owning a property. It took a further decade for women to receive the vote on the same terms as men with the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928 extending the vote to all women over the age of 21.

Little is known about Chester’s connection to the ‘Votes for Women’ movement, however the discovery of an article written in 1939 to celebrate the 21st anniversary of women’s enfranchisement, sheds considerable light on the activities and organisations in Chester dedicated to achieving votes for women.

‘Chester saw some of the activities of the suffragettes who worked for the cause with energy and enthusiasm, and were careful, as a rule, to keep within constitutional bounds.’

(Cheshire Observer, March 25th 1939, MF 225/74)

This sparked an idea! Given that newspapers were the principle means of communicating to a mass audience and the most widespread media form in the Edwardian age, I wondered whether it would be possible to piece together Chester’s suffrage past using old editions of local newspapers held on microfilm at the Record Office.I discovered a number of local newspaper reports detailing the peaceful activities of organisations that had set up branches in Chester, particularly the Chester Women’s Suffrage Society, the Women’s Freedom League and the National Union of Women’s Suffragist Societies (NUWSS). An article written by a ‘Lady Correspondent’ remarks that all branches of the NUWSS, including the Chester branch, stood for the ‘enfranchisement of women worked for on peaceful and law-abiding lines, and that the recourse to violence is destructive.’ (Chester Chronicle, 18th July 1914, MF 204/38).Unlike more militant organisations such as the Women’s Social and Political Union, evidence suggests that organisations in Chester concentrated on legal and peaceful means of drawing attention to their cause by arranging speeches, events and the sale of merchandise to raise funds. The Women’s Freedom League even opened a Suffrage shop at 45 St. Werburgh’s Street where they sold merchandise such as badges.

|

| Chester Chronicle, 13th January 1912, MF 204/36 |

|

| Chester Chronicle, 16th February 1918, MF 204/268 |

Despite the preference for legal and peaceful means of protest in Chester, Emmeline Pankhurst, founder of the more militant WSPU, visited the city in January 1912. Despite the Hall not being filled, reports indicate that Mrs. Pankhurst received a ‘good reception’. Speaking with ‘great clearness and… putting her points with telling effect’, Mrs. Pankhurst declared that she wanted ‘every human being, if possible, to have some control over the spending of taxation and the making of laws’. Mrs. Pankhurst also spent time defending militancy commenting that ‘it was not the reasonable patient person who ever got anything’ and posing the question ‘Were the women of Chester prepared to help?’

|

| Chester Chronicle, 13th January 1912, MF 204/36 |

The article I first found in the Cheshire Observer dated 1939 reveals that there was one particular incident that saw the events in Chester make widespread national news.

‘There was a notable incident however, when their zeal outran their discretion and they brought themselves in conflict with the law. It occurred in the summer of 1912, and the Prime Minister, Mr. Asquith, was the victim of their violence.’On his return from Dublin, Prime Minister Herbert Asquith paid a visit to Chester. Arriving at Chester Station on Saturday 20th July 1912, the Prime Minister made his way to the Town Hall to meet the gathered crowds.

(Cheshire Observer, March 25th 1939, MF 225/74)

‘About twenty past two there was a commotion among the crowd… The Prime Minister had arrived… The fleet of cars sailed into the Square almost noiselessly, and the third car, decorated with blue ribbons, contained the Prime Minister.’(Chester Chronicle, 20th July 1912, MF 207/36)

‘There was a spasm of violent excitement among the crowd as it stopped. Something had happened which not everybody could see, but everybody could see a stalwart policeman pounce on a protesting young woman and forcibly haul her off to the lock-up. She was a suffragette, a bag of flour had been thrown (it was said) at the Prime Minister’s car, and she had been arrested for it’.

|

| Chester Chronicle, 20th July 1912, MF 207/36 |

‘Instantly, P.C. Baker secured the lady, and at almost the same moment another lady was heard shouting and pushing through the crowd. P.C. Wakelin pushed her back… As the lady in custody was taken past his car on her way to the Police Office, she jeered at him, and the crowd returned the compliment to her.’ (Cheshire Observer, 27th July 1912 MF 225/35)

Reporting on the aftermath of ‘The Chester Incident’, the Cheshire Observer recounted events at the Police Court. Charged with the assault of Frank Clark who had been driving the car that was hit by flour, the assailant was identified as Mary Phillips, a journalist from Cornwall. Giving evidence, the Chief Constable asked ‘the Bench to make an example of the defendant.’ (Cheshire Observer, 27th July 1912 MF 225/35)

‘There was no doubt that the missile was intended for the Prime Minster. If Cabinet Ministers could not travel about the country without attempts being made to assault them, then the country must be coming to state of anarchy.’ (Cheshire Observer, 27th July 1912, MF 225/35). Despite denying the charge of assault and protesting that if she had intended to injure the Prime Minister or damage the car she would have used a more dangerous missile, Mary Phillips was found guilty. She had the choice to pay 5s. in fines and additional costs, or receive seven days imprisonment in the second division. She refused to pay the fine, but it was later paid by a ‘prominent Chester Liberal’ whose identity remains unknown still.

|

| Cheshire Observer, 27th July 1912, MF 225/35 |

By piecing together the newspaper articles above, we can come to understand that the women of Chester were engaged with the political campaign to give women the vote and furthermore, that the streets of Chester did witness militant action to advance this aim. 2018 marks 100 years since the Representation of the People Act 1918 gave the vote to around 8.4 million women over the age of 30 who met certain conditions, including owning a property. It took a further decade for women to receive the vote on the same terms as men with the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928 extending the vote to all women over the age of 21.

Thursday, 11 May 2017

Some Theatrical Entertainments in Chester in the18th and 19th Centuries