There’s nothing that gets our hearts racing more than being presented with a box of dirty, torn, and tatty plans and being asked to Conserve them! In this instance, a map box containing ten rolled bundles of drawings of the Heraldic Coats of Arms for the ‘new’ Queens Park Suspension Bridge in Chester (ref. ZCR/715/1-10).

What are the drawings of?

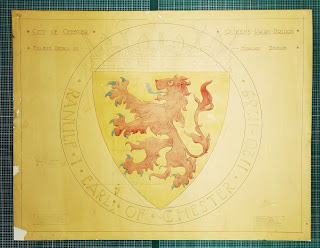

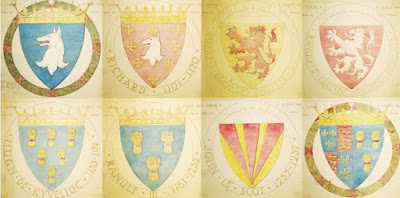

The first suspension bridge from the Groves to the new housing at Queens Park was built in 1852. This first bridge was replaced in 1923 by the Corporation at a cost of £7,000. These drawings are of the heraldic coats of arms of eight Norman Earls of Chester which decorate the arches above the bridge. The drawings are by architects F.A. Roberts and P.H. Lawson of 88 Foregate Street, Chester.Why conserve these plans when we have so many others that need our care?

Events, activities and exhibitions are being organised to celebrate the one hundred year anniversary of Queens Park suspension bridge during May and June of this year. These plans, along with other related material, have been chosen by our Archivists’ to support this work.

How were the drawings made and what condition are they in?

An outline of the heraldic shield encircled by a wreath was printed onto paper and used as a template for the drawings. The designs have been hand drawn at full scale and coloured. There are eight completed designs with a set of additional pencil drafts of the designs on tracing paper. Media used for the drawings include pencil (for outline and shading), water colour paint and ink.Once unrolled, we can assess the condition. Much of the damage has been caused historically by poor handling and storage. We find surface dirt, tears, missing areas (lacunae) and areas of paper degradation, especially along the top and bottom edges.

The conservation treatment consists of cleaning, flattening and repairing the plans so that they can be handled safely, without causing further damage, digitised and exhibited.

How do we remove the surface dirt?

The bread and butter of any Paper Conservators’ work is cleaning, and lots of it! It looks simple, but it takes years of experience (and sore fingers) to develop techniques that work effectively and that don’t cause damage to the original material.

These drawings were especially challenging to clean as the artist has used pencil for outlining and shading. We need to remove the general surface dirt whilst being careful not to remove the actual pencil. Using thin wedges of vinyl eraser we are able to carefully work around the pencil and remove the surface dirt.

How do we get them flat?

Next, we need to ‘flatten’ the rolled plans so that we can repair them. The drawings are placed in a large ‘damp-pack’ to introduce water vapour into the paper in a very controlled and gentle way. This in turn will ‘relax’ the individual paper fibres and make the paper more pliable. Once damp, they are placed under thick sheets of blotting paper and covered with sheets of Perspex, then weighted down to flatten them.

The humidification chamber (damp pack) we use is made up of a layer of clear polyester, a wet layer of capillary matting and a layer of Sympatex (a breathable waterproof membrane) on the top. The same three layers are then placed over that in reverse order, and the document placed in the middle to receive the water vapour and ‘relax’!

How do we mend the tears and fill in the lacunae?

Most of the drawings have some minor tears that need repairing, but a few of them, including ZCR/715/4 for Ranulf I, Earl of Chester, 1101–1120, have suffered more substantial damage. This long horizontal tear was likely to have been caused by someone attempting to unroll the plan. This sort of damage is commonly seen in large paper documents such as maps and plans that have been stored rolled.

The process begins with cooking some fresh wheat starch paste to use as an adhesive for the paper repairs, which we prepare in the Conservation studio. After cooking and cooling the paste, we sieve it three times to create a super smooth and sticky, but fully reversible paste.

It can be difficult realigning long tears so that the image area joins up accurately, even when the paper appears perfectly flat. Paper can be affected by levels of high humidity, so any exposure in the past, and during the humidification process can alter the placement of paper fibres making it difficult and sometimes impossible to join them perfectly.

We apply paste using a small brush to the edges of the tear, working on the image side (the recto) to check on alignment, and work along a small section at a time. This is sometimes called ‘Chasing the tear’! When the edges are joined, we turn the drawings over and adhere a section of Japanese repair paper to support this area from the back (the verso).

How do we consolidate these repairs?

Adding a support layer on the verso is essential when repairing tears as it adds strength to weak and degraded areas and allows the repaired paper to flex normally without any further damage being caused. We select a Japanese paper (Kozo Shi) of lighter weight but similar colour to the original document. The repaired areas need to be clearly visible but also be sympathetic to the original material.Handmade Japanese papers are ideal as they have long fibres and keep their strength when wetted out. We use a mattress needle to score the repair paper to the shape and size we need, wet with a water brush and tear the support out. The resulting long fibred edges make for a strong and sympathetic support layer once pasted down.

What about the lacunae?

We add repair paper to infill and strengthen missing areas. This also includes replacing original material that has become detached. Using a heavier Japanese paper (Bunkoshi) that equals or is a bit lighter than the original and working on a light (illuminated) table; we score the exact area missing with a mattress needle.

We then soften the paper fibres using a Rotring pen filled with water and tear out the infill, add paste to the reverse and adhere in place to fill in the missing area. The repair to this plan is finally complete after the repairs have dried and trimmed with a sharp scalpel. As a final protective measure they are placed into transparent polyester sleeves.

We still have a bit of work to do until they are all conserved and accessible, but they will be ready in plenty of time for the upcoming events and activities. We wait, in eager anticipation, for the next box of tatty items to appear in our conservation studio!

To hear about future events subscribe to our newsletter at www.cheshirearchives.org.uk

.jpg)

.jpg)