1945

After the war there was a need to rebuild war damaged areas across the country. Chester had been largely unaffected by the architectural damages of war but was in need of an overhaul to rectify some of its problems. A Plan for Redevelopment was written up by Charles Greenwood in 1945. It focused on controlling the city centre traffic and dealing with old housing with undesirable living conditions. About 2500 houses over 100 years old were condemned.

After the war there was a need to rebuild war damaged areas across the country. Chester had been largely unaffected by the architectural damages of war but was in need of an overhaul to rectify some of its problems. A Plan for Redevelopment was written up by Charles Greenwood in 1945. It focused on controlling the city centre traffic and dealing with old housing with undesirable living conditions. About 2500 houses over 100 years old were condemned.

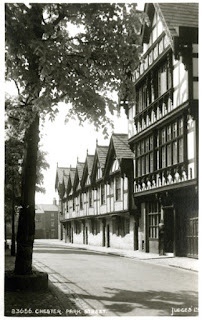

|

| Chester, Francis Street. Image Courtesy of Chester History & Heritage. Image Bank ch5860 |

Many recommendations in the report were used as the basis for future changes, but lack of funding meant that redevelopment was slow and ineffective in reaching the goals over the short term. But it was the beginning.

1960s

In the 1950-60s there was concern that the historical face of Chester was being slowly obliterated which sparked the creation of Chester Civic Trust in January 1960. After their formation, the Chester Civic Trust immediately had to step in regarding The Blue Bell. The Blue Bell in Northgate Street was in danger of being demolished, but the Chester Civic Trust put forward their case that it should be kept and restored. The council agreed to keep the building and to fund the restoration project themselves. This was one of the first major wins for the Trust.

Around this time, lots of new development projects were being proposed. This included small and larger tower blocks. Chester Civic Trust tried to fight to stop these going ahead. Those approved with only minor consideration for the views of the public included Commerce House (now demolished to make way for Storyhouse); The Police Headquarters (now demolished to make way for the ABode hotel and Chester West and Chester council HQ) and the replacement for Clemences restaurant on Northgate Street.

Chester Civic Trust did however make some headway and advised the council not to demolish a number of historically important houses on Queen Street and to acquire and renovate the Nine houses on Park Street, which still stand today. The idea of preserving and conserving buildings had been brought to the forefront of people’s minds.

|

| Chester: Park Street View of the Nine Houses. Image Bank c10324 |

1967 brought the Civic Amenities Act. The Act required local authorities to start to recognise groups of buildings with historical value and designate them as conservation areas. Most of the centre of the city was designated. Previously, historical buildings were at risk of becoming derelict and demolished with little money or support to stop this. The aim of the Act was to conserve groups of buildings which made a town, city or village unique and ensure their value was not overshadowed by new developments.

In the new conservation areas, additions to properties such as extensions were regulated and trees within the areas were occasionally granted historical importance and not allowed to be felled. Also, any “proposed developments must preserve or enhance the special architectural or historic character of the conservation area. This does not specifically exclude innovative proposals but they must be sympathetic to their context.”

Out of this Act came four Historic Town Reports (one each for Bath, Chester, Chichester and York). Chester commissioned their Historic Town Report to be undertaken by Donald Insall Associates entitled ‘Chester, A study in Conservation’.

|

Cover of Donald Insall’s report “Chester: A Study in Conservation.” Taken from the Insall Collection at Cheshire Archives and Local Studies. |

Sir Donald Insall and his team identified key streets and areas in need of conservation efforts. Photographs were taken, voice recordings of initial impressions made and rough conservation costs drawn up of properties at risk. The photographs produced for this work are now held on-site at Cheshire Archives and Local Studies.

The report considered the most problematic area to be Bridgegate. A base of operations was set up in the area, and the need for swift restoration was highlighted when the office’s roof collapsed!

Gamul House and Gamul Place were some of the first chosen to be preserved and extensive work was carried out in this area and the rest of Bridgegate. A short film ‘The Conservation Game’ was produced and shown on television to highlight the considerations over this period and to follow the renovations of the buildings.

The report considered the most problematic area to be Bridgegate. A base of operations was set up in the area, and the need for swift restoration was highlighted when the office’s roof collapsed!

Gamul House and Gamul Place were some of the first chosen to be preserved and extensive work was carried out in this area and the rest of Bridgegate. A short film ‘The Conservation Game’ was produced and shown on television to highlight the considerations over this period and to follow the renovations of the buildings.

|

| Gamul House, Lower Bridge Street, Chester : following restoration |

|

| Houses in Shipgate Street, Chester before restoration |

|

| Houses in Shipgate Street, Chester following restoration. Taken from the Insall Collection at Cheshire Archives and Local Studies. |

More recently, conservation work was undertaken on the City Walls in 2013 and on Eastgate and Eastgate Clock in 2014. Modernisation and conservation of buildings around Chester Station has also been undertaken after some had fallen into disrepair. The Civic Amenities Act 1967 has made a difference to the cityscape of current Chester with the spirit of conservation continuing on.

More photographs from the Insall Collection will be shown on our Twitter page @CheshireRO for #civicday 17th June 2017. The whole collection of images taken for Chester’s Historic Town Report are held by Cheshire Archives and Local Studies and we are working to make them accessible to the public as soon as possible.