Almost all family historians will have made use of the census at some point in their research. Censuses can tell you when and where your ancestors were born, the address where they were living, their occupations, and their relationships to people living in the same household. Later censuses may even tell you how long they’d been married, how many children they had, and even how many rooms were in their house.

In England and Wales a census has been taken every ten years since 1801 (with one exception, which we’ll come to later). Were you asked last year to complete an online census form? We’ve come a long way since the very first census in 1801, when local parish officers were dispatched in order to, quite literally, count every man, woman and child, before posting the handwritten returns off to the census office in London, so that they could be collated and printed in large statistical volumes.

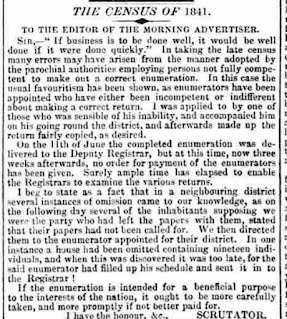

From 1841 onwards the administration of the census passed to the General Register Office, which had been set up just four years previously to oversee the introduction of civil registration of births, marriages and deaths. This was the earliest census to officially record personal information, such as names and occupations (although, extremely rarely, draft notebooks with this information survive from 1831 or earlier). Every householder was asked to complete a form with details of everyone at home on census night; the details would later be copied by clerks into a separate series of books, and the original forms destroyed. However, this process didn’t always go entirely to plan.

Although the 1841 is the earliest census we now have access to, it provides less information than its successors: the ages of everyone over 15 were supposed to have been rounded down to the nearest five years (although this rule wasn’t always strictly followed), and people weren’t asked for their exact place of birth: only whether they were born in the same county, in Scotland, Wales or Ireland, or overseas.

From 1851 onwards we usually find more precise information concerning ages and birthplaces, although it isn’t uncommon to find ancestors ageing rather more or less than ten full years in the intervening decades (sometimes even miraculously becoming younger from one census to the next!). People couldn’t always be relied upon to give accurate information, and I have one ancestor whose birthplace is different in every census in which he appeared. The census officials had no way to check whether the information they were given was correct, and people then were no less wary of providing their personal details to the authorities than they are today. For example, in the nineteenth century there was an incentive for people to claim that they were born in the same parish where they were living, since the poor laws of the time could see them returned to their ‘home’ parish if they fell on hard times.

In order to reassure the populace that the information given to census officers wouldn’t be used against them (provided it wasn’t intentionally wrong or misleading), guarantees were made that everyone’s details would remain confidential for 100 years; this undertaking became enshrined in law in 1920.

During the twentieth century, the earliest censuses were therefore released to the public one hundred years after they were taken – usually in the January of the following year. Initially, researchers would have to travel to the Public Record Office (now The National Archives) in London to look at the original paper returns, which had been bound into thousands of large volumes. In the 1970s these were microfilmed and distributed around the country (and even around the world), to provide greater accessibility for the growing band of family historians.

The 1891 census was the first to be released exclusively on microfiche, rather than the more cumbersome microfilm, while the 1901 and 1911 returns could be accessed through the internet shortly after their release. This was especially important in the case of the 1911 census, which came in a different format, showing each household on a separate page (in fact these were the original forms completed by each householder, now preserved for posterity). Thus the number of images from 1911 is vastly larger than for 1901. The earlier censuses back to 1841 have also now been digitised, and are accessible through various pay-per-view sites on the internet, where they can also be searched by name or address.

No doubt you’ll have realised that the release of the 1921 census must be imminent - the launch date is 6 January 2022. Initially the returns for England and Wales will be available exclusively through Find My Past, who have been The National Archives’ commercial partner in carefully digitising and conserving over 20 million pages – containing almost 38 million names – in full colour, and all completely indexed. The 1921 censuses for Scotland and Northern Ireland will be released separately by their own national archives.

The format of the England and Wales returns is very similar to the 1911 census, so we’ll be able to see the individual householders’ forms, in their own handwriting, which occupy more than a mile’s worth of shelving at The National Archives. The 1921 census also provides some extra details, such as the places where people worked (not just their occupation), and whether the parents of children under fifteen had died. Ages were also to be recorded in years and months, rather than to the nearest year as in previous censuses, hopefully making them a little more accurate.

The census will be free to view online at The National Archives in London, at Manchester Central Library, and at the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth. However, everywhere else you will need a personal Find My Past subscription, which will allow you to see the images on a pay-per-view basis. Until Find My Past have recouped the expense they incurred in their digitisation project, unfortunately you won’t be able to access the 1921 census free of charge at the Cheshire Record Office or in the county’s libraries, as you currently can with the earlier censuses and the rest of their collections. For full details see:

If you’ve already traced your family back a few centuries, you may wonder whether it’s worth bothering with a source that’s so comparatively recent. But history can be full of surprises, and it’s only by collecting as much information as possible about our ancestors, or the places where we live, that we can piece together a complete picture of where we came from.

Finally, if all this has made you giddy with excitement at the prospect of future census releases, then you may have to be a little patient. I mentioned that the census had been taken every decade except one – which was 1941, due to the Second World War, during which the returns for the whole of the 1931 census were completely destroyed by bombing. So the 1951 census will be the next to come out… and we’ll have to wait until January 2052 for that!