We have original photographs of royal visits to Cheshire throughout the 20th century, from King Charles as Prince of Wales back to his great-great-grandfather King Edward VII at the start of the 1900s. Many are available to search online at Cheshire Image Bank. This selection shows the new King (then Prince of Wales) at Chester Castle in 1973; Queen Elizabeth II visiting Chester Royal Infirmary in 1957; King Edward VIII (also as Prince of Wales) visiting Nantwich in 1926 and King George V meeting some Brownie Guides in Frodsham in 1925.

Our Local Studies collection holds a wealth of books and pamphlets commemorating such visits and marking other significant occasions. There is extensive material about Queen Victoria, for example. There are documents linked to major events, such as the Mayor of Chester’s Proclamation of Accession (ref: 226498), a limited edition book of The Celebrations at Winsford of on the Occasion of the Jubilee of HM Queen Victoria (ref: 201682) and pamphlet How Loyal Macclesfield and the District Celebrated the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria 22nd June 1897 (ref: 115520). More widely, we have archives on a range of items linked to Victoria - anything from her diamond jubilee being marked with Chester’s famous Eastgate Clock, to the opening of places like Victoria Park in Widnes in her honour.

We hold letters patent (a written order issued by a monarch) from Queen Victoria in 1845 to the Mayor of Chester (Richard, Marquis of Westminster) whom she addressed as ‘our most dear cousin'. They were attached with a great seal made of leather, one side of which has an imprint of the queen enthroned, the other shows her on horseback.

The seals of many other monarchs are contained in our collections - the earliest dates from the reign of King Henry II in 1175 or 1176 (ref: ZCH 1). Only a fragment now remains - perhaps understandable for something made 850 years ago!

This is the seal of King Richard III, from a medieval charter granting remission of Chester rents due to the King. The seal constitutes the signature of the monarch, and shows Richard with his sword and shield on a horse (ref: ZCH 30).

The Interregnum of 1649 to 1660 saw a break between Kings Charles I and Charles II, and Oliver Cromwell became Lord Protector. We have some archives from that period such as this deed (ref: DDX 181/3) headed ‘Oliver, Lord Protector’ and the unusual accompanying seal depicts an image of Parliament.

Sometimes a seal has not survived well, but the documents they were attached to remain in good condition, like the examples below.

The one above left is a charter that includes a portrait of King Charles II in oils. It is embellished with ornate gilt designs and dates from 1685 (ref: ZCH 39). The other charter (above right) dates from 1803 in the reign of King George III (ref: ZCH 42) - it has engraved borders and also has a portrait of the King in the initial letter.

We are the proud custodians of some 'letters close' of Queen Elizabeth I - these are unopened letters dating from May 1583 (ref: DSS 3991/329). As opposed to letters patent, letters close were personal, and were delivered folded and sealed so only the recipient could read their contents. Elizabeth’s signature is visible on other documents however, such as this one from our Cholmondeley Estate collection (ref: DCH/X/15/4). The document is bound in a leather volume embossed with the initials ‘ER’ – not dissimilar to those used in the cypher of Queen Elizabeth II that we’ve been used to seeing over the past 70 years, except from the 1560s!

Other monarchs’ signatures are held on a variety of documents at Cheshire Record Office too – for instance, the writing on the top left of this document is the signature of Elizabeth’s father, King Henry VIII – it is a warrant to release the Abbot of St Werburgh’s Cathedral from financial obligations, and dates from 1510 (ref: EDD/3913/20).

Queen Anne’s handwriting is a little easier to read – this is her signature on a Royal Commission relating to the governor of Chester castle dating from 1702 (ref: DSS 1/3/37). The same can be said of King James I’s signature, shown on this 1609 correspondence about game in Delamere Forest. (ref: DAR/A/3/13)

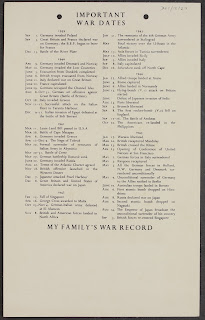

Coming a little more up to date, a copy of George VI’s signature was included on a card sent to schoolchildren to commemorate the official Second World War Victory Celebrations, which took place on 8th June 1946. The back of the cards had space for children to note down their own family’s war record. An example is held in our collection from Boughton St Paul’s Girls and Infants school in Chester (ref: ZDES 12/27).

There are many Cheshire documents related to the Coronation of each monarch (except of course Edward VIII who abdicated before he was crowned) from souvenir programmes like those produced by the Borough of Crewe to commemorate the coronation of King George VI in 1937 (ref: 230556); a printed handbill celebrating the coronation of Queen Victoria in 1838 with a programme of events in Chester, including a procession and a display of fireworks on the Roodee, ref: 231779); and minutes and papers of Congleton’s preparations for the coronations of King George IV, Queen Victoria and King Edward VII, from 1820 to 1902 (ref: LBC/47/6). The excerpt below shows careful planning for a public dinner and tea party in 1838. And to celebrate the platinum jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II in 2022, Cheshire Archives and Local Studies published a blog which includes lots of 1953 coronation memorabilia from across the county.

Below is a page from a whole volume of minutes of the Coronation Committee set up by Alderley Edge Urban District Council to plan their proceedings for King George V’s coronation in 1911 (ref: LUAd/2035/6). Men of the village are recorded in committees covering every aspect of the day: from a general committee to a finance one, another for catering, one for sports and procession, another for decorations and medals - and even a bonfire and fireworks committee. Every detail was planned, discussed and scrutinised – even deciding the different categories of races, which included one for people named George or Mary like the new king and queen, a smoking race (we aren’t sure either!) a 50 yard race category for married women, even a ‘veterans’ race – for people aged over forty!

For anyone taking part in community celebrations for King Charles’ coronation, we have photographs of previous generations in Cheshire doing a similar thing. This Image Bank selection shows a lorry in Frodsham decorated for the coronation of George VI, a Malpas street party celebrating that of George V, and coronation celebrations for King Edward VII in Wilmslow in 1902.

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)