The early to mid-1840s saw Britain in the grip of ‘railway mania’. Low costs, speed and convenience made rail travel very popular - and lucrative. New railways for passenger and freight lines were quickly developed.

At that time the only communication links between London and Ireland were by horse-drawn coach or by sea. Both routes were made long and difficult by poor roads and harbour facilities. A railway that would take government mail dispatches more quickly to Ireland was well-supported in Parliament and the Chester and Holyhead railway was authorised in July 1844.

George Stephenson surveyed the route, which would extend the Chester to Crewe line along the North Wales coast. His son Robert Stephenson was the engineer, with Francis Thompson the architect and Thomas Brassey the contractor.

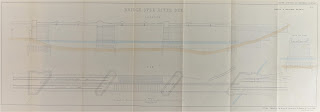

Building the railway was both challenging and extremely expensive. It required bridges over the River Dee, the River Conwy, and the Menai Strait at Anglesey. Progress on the railway was slow but the first section, between Chester and Saltney, opened in November 1846. It included a 250 ft long cast iron and stone bridge, designed by Robert Stephenson, that crossed the River Dee near to the Roodee. The bridge was opened with great ceremony.

But just six months later, on 24th May 1847, disaster struck. As a passenger train was crossing, the final span of the bridge collapsed. James Clayton, the driver, managed to get the 30-ton locomotive and its tender onto the far bank, but all four carriages and the guard’s van fell over 30 feet to the river below. Of the twenty-five people on board, five (the fireman and four passengers) were killed and fourteen were injured. Both local and national newspapers reported on the shocking and sensational incident.

Robert Stephenson was criticised for the bridge’s failure, threatening his reputation. An inquest was held in Chester and witnesses testified to seeing a fracture appear in the cast iron girders before the collapse.

Newspapers followed the case closely. After two weeks it was found that no one person was to blame, however the jury expressed concern about the use of ‘so brittle and treacherous a material as cast iron’.

Following the disaster, Robert Stephenson used only wrought iron on his railway bridges, including the Conwy Railway Bridge and the Britannia Bridge over the Menai Strait. Both were impressive engineering feats, particularly the Britannia Bridge at over 1500 feet long and standing over 100 feet above the water. On 5th March 1850, Stephenson himself laid the last rivet on the bridge and drove a test train across it, marking the completion of the Chester to Holyhead Railway.

The railway had a major impact on the city of Chester as a regional centre. The original Chester railway stations on Brook Street were little more than wooden shacks and converted houses. To cope with the growing traffic, the Chester and Holyhead and other rail companies agreed to build a new larger station. It was designed by Francis Thompson and built by Thomas Brassey. The station opened on 1st August 1848 to the acclaim of the local population.

The first Irish Mail train left the new station for Holyhead that same day. With the transportation of goods to Ireland, and an increase in trade from North Wales, Chester regained a good deal of the prosperity it had lost following the silting up of the River Dee.

The line was fully opened to passengers on 18th March 1850 and was immediately popular. It enabled people to travel cheaply and quickly to holiday and tourism destinations in North Wales and Ireland. In 1858 a branch line to Llandudno, one of the early favourite holiday destinations, was opened. Throughout the late 19th and 20th centuries travel by rail to holiday destinations on the North Wales coast continued to grow.

Today the cause of the River Dee Railway Bridge collapse would be called metal fatigue. The bridge was rebuilt several times and eventually replaced with a completely wrought iron bridge in 1870. Robert Stephenson’s wrought iron Conwy Bridge still stands today, whilst the original Britannia Bridge was only replaced in 1980 after being severely damaged in an accidental fire. The railway line itself continues to be heavily used by passengers as part of the North Wales Coast Line.

175 years on from the tragic River Dee Bridge disaster, the greater story of the Chester to Holyhead railway is one of success.

These railway records and more are available to view at Cheshire Record Office in Chester. Transcriptions of several Crewe Works and railway companies’ staff registers can also be found at our web site here for Crewe, and here for four companies covering parts of Cheshire, Shropshire, Hereford and Wales.

Keep a look out on our Instagram and Twitter pages for more from our railway collections soon!

No comments:

Post a Comment