Read Part 1 of A Farmer's Life: The Diary of James Higginson aged 57½ here.

The diary covering 1817-19 gives us an insight into a

particular 15 months in James Higginson’s life but what else do we know? We can tell from his writing that he was

educated. His diary entries show that he

employed several men, his financial dealings indicate he was reasonably well

off (he loaned money to friends and received dividends), he was able to take time

away from the farm to visit his brother who lived some distance away, and we

know he liked to socialise, but we hold other sources that add more

information.

At the time this diary was started, James and Mary would

have been 57 and 42 years old and had been married for 17 years. They had three sons, Charles, 16, who worked

on the farm, Edward 11, and James, 7. We

know this because their marriage, their burials, and their children’s baptisms are

in the parish registers for St Bartholomew, Barrow.

When James died in 1835 at the age of 75, he left

everything to Mary. We have his will which he signed just a few days before he died. By then, the man who had written so neatly in

the small notebook was too unwell to sign his name and could only make his

mark.

We know that Mary continued at the farm until her death

in 1861 as the Tithe Apportionment of 1839 lists her as Occupier. Searching our Tithe Map site using her name

will show you the extent of the land the Higginson’s farmed.

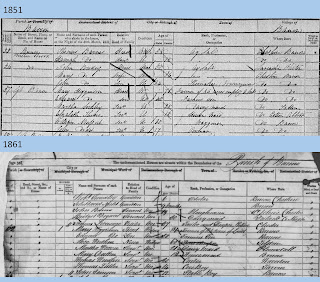

We also know that by 1851 her sons Charles and James no

longer lived in the family home. Census

returns for 1851 and 1861 show that her middle son Edward still lived with her

and helped run the farm. In 1851 the

household consists of: Mary, Farmer of 86 acres, Edward, Farmer’s son, plus a

Dairymaid, Housemaid, Waggoner and Cowman.

The next census in 1861 was the year Mary died. She was 86 years old and presumably needed

more help running the household as her niece Alice Woodier is included as

Housekeeper. There was also a Dairymaid,

Housemaid, Carter, Cow Boy (aged 14) and Stable Boy (aged 12).

The newspapers of the time help to flesh out events that

James only mentions in passing such as the deaths of Princess Charlotte and

Queen Charlotte, mentioned previously, giving us a taste of life in the early 19th century.

One particularly gruesome event was recorded briefly on

Saturday 9th May 1818. It

came between a sentence about his cows and a note on the price of butter: ‘My

wife & her Son James at Chester seeing the Two men to suffer’. Hold on - what? The Chester Courant of 12th May

1818 carries a report of the execution by hanging of 2 men, Abraham Rosthern

and Isaac Moors. Rosthern had stolen

items from his employer, namely 7 pictures, 1 looking glass, 5 silver

teaspoons, 1 pair of silver sugar tongs, a drinking horn, a quantity of jaconet

muslin, gold thread and several other articles.

Moors had broken into a house and stolen various articles of linen and

drapery.

The Courant reported that a great crowd came to watch the

executions, estimating that 6000 people attended. In amongst them were Mary Higginson and her

youngest son James. The parish records

have James being born and baptised in August 1809, so in May 1818 he would only

have been 8 years old! Whether he was

brought along as a form of entertainment or to terrify him into living an

honest life, we’ll never know.

All of these items and more are available to view at Cheshire Record Office in Chester.